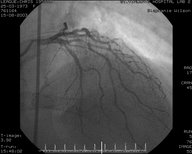

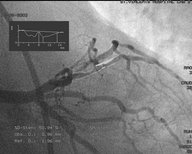

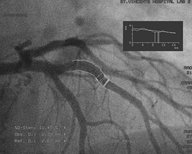

An annotated screen shot from the computer in the cardiac cath lab.

Here, the computer has estimated the shape of an artery where

constricted blood flow can be seen. The measurement shows that 51% of

the 1.96mm diameter is blocked; this is a 76% blockage in area.

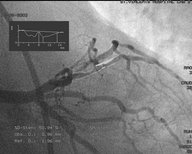

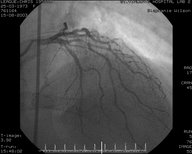

This is the worst—a 93% blockage.

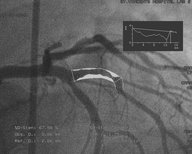

An 89% blockage in another branch of the same artery.

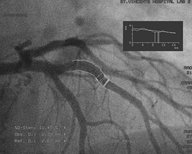

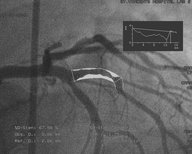

Success—you can see from the branching pattern that this is the same

artery that has an 89% blockage above, but now it is down to 20%.

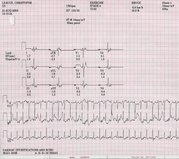

This is the ECG that was produced during my stress test (Bruce

protocol, stage 4).

|

At St. Vincent’s

I was examined quickly in the ER, but then had to wait around in a

gown for the better part of the day… waiting, anxiously, to hear that

I was not having a heart attack and I could go enjoy the rest of my

holiday. Unfortunately, my blood test came back with elevated

troponin, which is released into the blood stream when the heart

muscle suffers damage.

This result finally got the attention of a cardiologist, and before

long I was rushed to the cardiac cath lab for emergency angiography…

they guided a catheter into my femoral artery, and maneuvered it up

into my heart, so they could X-ray and tinker with it.

Although the procedure was relatively painless, it was nevertheless

the scariest experience of my life. Especially during preparation:

they placed gel-laden orange pads on my chest, in case of cardiac

arrest. (When they carted me around for various tests, I always went

with a battery-operated EKG monitor and defibrillator…) Amidst all the

tinkering, all I could really feel was a severe hot flash whenever

they released the X-ray dye.

Anyway, it turns out I had a 93% blockage in the LAD (left anterior

descending) coronary artery. :(

Now that I’ve got you on the edge of your seat, I’ll cut the story

short with the good news. As part of the same procedure, still

working just through the femoral artery, they enlarged the bad artery

and inserted two stents—small metal scaffolds that keep it open.

Moreover, these are the new Cypher stents, that are coated with

medication to prevent them from blocking again.

The procedure was successful, and I recovered in a private room with a

view of the city, closely monitored by clever machines and helpful

nurses. Before leaving the hospital, I had an

echocardiogram (a kind of sonogram) where they determined that my

heart was now working quite well. They said it looked like the stent

was applied before much damage could occur.

For medical folks and fellow nerds, the technical diagnosis was “very

mild anteroseptal hypokinesis, left ventricular ejection fraction:

60%.” (Apparently, a normal ejection fraction at rest is 55–65%)

Since he knew I was a computer scientist, one of the interventional

cardiologists burned for me a CD-ROM of the pictures and movies they

took during angiography. You can see the results on this page. (I’m

also thrilled to report I was able to extract and process the DICOM

medical image format using entirely open-source tools on Linux, specifically MedCon and ImageMagick.)

Prognosis

I left the hospital, and slowly resumed tourism. Before leaving

Sydney though, I had another test that gave me much more confidence:

an echocardiogram after spending 10 closely-monitored minutes

power-walking and jogging on a treadmill, which brought my heart rate

to 196 bpm. The cardiologist said my heart looked relatively healthy,

and that I should resume (i.e., start) exercise.

We then flew from Sydney to Melbourne, and had a relatively normal last

5 days of ‘vacation’. Now I’m safely back in New York, and I’m taking

blood thinners, blood pressure meds, cholesterol meds, etc. But I’m

really feeling much better.

I haven’t exactly worked out yet the philosophical implications of

being by far the youngest patient in the cardiac ward, and what that

means for my life expectancy. But all signs seem to indicate that, if

I manage my risk factors well, I should be fine. In balance, it might

even be good that I had this early ‘warning’.

|